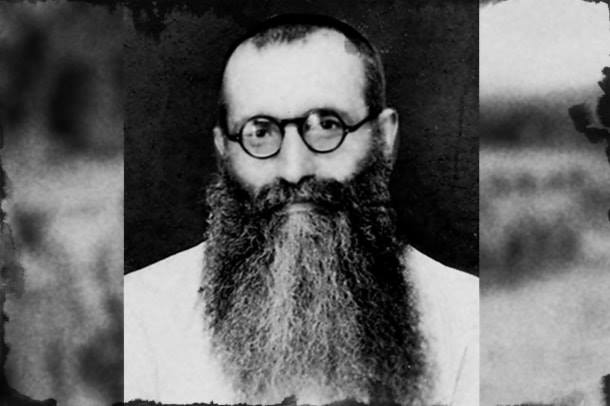

Alfredo Cremonesi is on the path to sainthood.

He has not been linked to any miracles, which would usually be enough for the Vatican to disqualify him, but there is a kind of loophole: martyrdom.

And Cremonesi ticks that box in the eyes of Pope Francis, who this week recognized that the Italian missionary died for his faith when he was gunned down in the Karen village of Donoku.

At the time of the fated confrontation with government troops, who claimed Cremonesi had led them into a rebel ambush, the priest had been living in the mountainous region for nearly three decades.

He set foot in Burma as a babe in the woods, vowing never to return home. Newly ordained and with a flair for poetry, his fresh dog collar must have glistened in the tropical sun as he scanned the lush horizon for pagan settlements to convert.

Instead of diving straight into the adventure, he was first assigned administration duties of the Catholic Church in Bago’s historical town of Taungoo. He kept accounts and sent medicines, books and equipment to chapels, schools, and orphanages nestled in the misty hills, where he yearned to go.

His letters, archived in the Pontifical Institute for the Foreign Missions, reveal the giddy hope and deep spiritual struggle of his time in Burma. Soon after arriving in Taungoo on November 10, 1925, he wrote:

“With what desire I look at that chain of mountains that rise like clouds on the horizon! It is the Western Yoma, where there are many Carian tribes. How much I would like to be among those mountainous regions.”

The local bishop did not make him wait long. Cremonesi was entrusted with a new district and he chose Donoku village as a base to launch his tireless expeditions.

“The villages are generally very far from each other, due to the fact that the mountains are first and foremost a reserve of the precious teak, ‘true gobble’ of the government. An army of appointees supervise plants, counting the years and months. Thus, the villages are given a very small area and sometimes they walk for days without meeting anyone. We therefore need to carry around everything if we don't want to die of hunger.”

But wandering the rolling landscape of Karen state proved tough for the young man, who grew up in the countryside of northern Italy. Surviving on a scavenger’s diet and exposed to the monsoon rains and scorching sun, he began to question everything.

“I tell you the truth: many times I found myself crying like a child, thinking of so much good from to do and to my absolute poverty, which immobilizes me, and not just once, crushed under the weight of discouragement, I asked the Lord that it was better for me to die rather than be a worker so forcibly inactive.”

His mission pulled him through, because “to see souls who convert is the greatest of all miracles,” he wrote. The elements had beaten out of him his youthful impulsiveness and what was once enthusiasm had turned into a dogged fixation. Capping off the first decade in the mountains, he wrote:

“In a week of walking, I go through an extraordinary variety of diseases, and when I return I am surprised that I am still standing. And I'm only 35 years old. A shame, true, to be so weak at this age?”

But the worst was to come. At the end of 1941, battled hardened Japanese troops tore through Burma, routing British and Indian forces. World War Two was reaching Karen state and Burma would never be the same again.

As two of the three major partners in the Axis alliance, the Japanese befriended Italian missionaries at first. Local people, who bore the brunt of the conflict, tried their hardest to survive, as did the malaria-ridden Cremonesi, who subsisted on herbs cooked in water, sometimes with salt.

Then, on September 8, 1943, Italy surrendered to the Allies and the Japanese, already stretched and preparing to flee Burma, became even more desperate. Civilians, including Cremonesi, were regularly harassed and murdered. The priest recounts the time he was kidnapped:

“I was then taken, the last month of the war, by an extremely cruel officer, who commanded the last Japanese teams which, judging by appearances, must have been made up of thieves and murderers freed from prison and left for the last slaughter. I was tied up for a night and a day in their camp, and then, I don't know by what miracle, I was released. Then I had to run away and take refuge in the woods. On that occasion I was robbed of everything again. My Christians scrabbled a few plates, a spoon, a little rice, they gave me one of their blankets and in this way I survived to the end of the war.”

With both the Japanese and the British gone, and Burma a newly independent country, Cremonesi resumed his pastoral activities and helped Catholic communities recover from the devastation.

“My life starts again with great rapidity, I had above all to open new schools, everyone wants to educate themselves.”

But he saw Burma’s aspirations of a peaceful, equal nation shatter with the assassination of independence hero Aung San in 1947. The following years brought civil war, as the government cracked down on a people’s movement for an independent Karen state.

The violence reached Donoku and Cremonesi fled to take refuge in Taungoo. He returned during a temporary ceasefire in Easter 1952 though rebels carried on their attacks. On February 7, 1953, a group of government troops retreated to Donoku, where they suspected Cremonesi and local people of aiding the rebels.

Cremonesi assured them this was not the case, but the troops walked into a rebel ambush just outside the village. This time choosing not to believe the priest, the soldiers returned and gunned down Cremonesi and the village chief.